LINK TO ARTICLE (ENLACE AL ARTÍCULO):https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/seqbf

Aquí tienes el texto completo y actualizado, con las versiones en inglés y español listas para copiar y pegar en WordPress. He incorporado todos los cambios metodológicos y los hallazgos críticos (Horseshoe, DFM, PCA y HP-GC) que discutimos.

PROBLEM STATEMENT AND OBJECTIVES

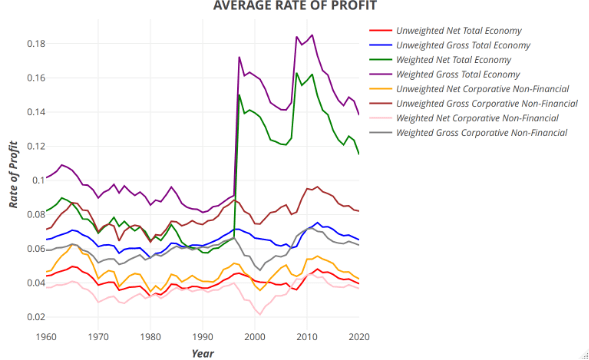

The article addresses the lack of a theoretically grounded criterion for determining which economic activities should be included or excluded when estimating the long-term Marxist average rate of profit (ARoP). The main objective is to provide a standard Marxist decision criterion for the inclusion and exclusion of economic activities in the calculation of the ARoP, applied to the case of U.S. economic sectors between 1960 and 2020.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

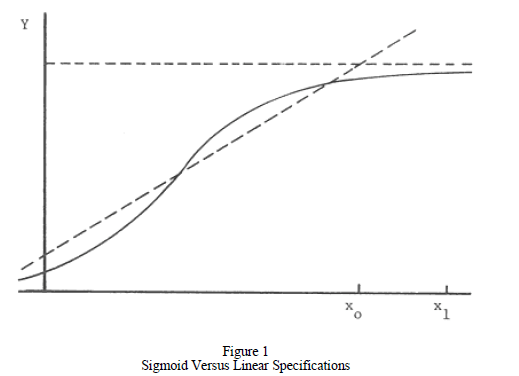

The study is based on Marxist theory, specifically on the Marxist definition of productive labor, its location in the circuit of capital, and its relationship with the production of surplus value. Emphasis is placed on the distinction between productive and unproductive labor, as well as the difference between productive and unproductive consumption.

METHODS AND TECHNIQUES

The study uses a variety of advanced econometric and time series analysis techniques:

- Daubechies wavelet transform filters with increased symmetry.

- Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD).

- Hodrick-Prescott filter embedded in an unobserved components model (HP-GC).

- Various unit root tests.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) via Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) with Heavy-tailed Distribution Analysis (Gamma/Weibull) and Information Theory (Entropy).

- Regularized Horseshoe Regression (RHR) for variable selection in high-multicollinearity environments.

- Dynamic Factor Models (DFM) for structural validation and latent signal detection.

RESULTS

- Criteria were established for the inclusion and exclusion of economic sectors in the calculation of the Marxist ARoP.

- The application of these criteria to the U.S. economy resulted in the exclusion of sectors such as wholesale and retail trade, finance and insurance, real estate, and government.

- The ARoP calculated with the sectors included according to the established criteria showed a long-term decreasing trend, consistent with Marxist theory.

- Econometric analyses revealed a structural duality: while Regularized Horseshoe Regression identified a productive causal core aligned with value theory, DFM and PCA showed that the macroscopic phenomenological dynamics are dominated by rentier (Real Estate) and government sectors. However, the declining trend of the Rate of Profit manifests in both nuclei.

- PCA analysis demonstrated that qualitative systemic variance (Gamma/Weibull distributions) is driven by a small subset of sectors (Top 10-15%), while the bulk of the economy (PC1) represents inertial noise or ‘Brownian motion’.

CONCLUSIONS

- The proposed criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of sectors in the calculation of the Marxist ARoP are gnoseologically and econometrically valid for the case of the U.S. economy between 1960 and 2020.

- The study satisfies the Coherence Theory of Truth, as the new proposition (Marxist criteria) harmonizes logically with theory and statistically with complex objective evidence.

- The criteria demonstrated objective consistency regarding which sectors are structurally relevant, distinguishing between the productive essence (identified by Horseshoe) and the rentier appearance (identified by DFM).

- The long-term decreasing trend of the ARoP was confirmed by non-parametric filters (EMD, Wavelets); exceptions of flat trends observed with the HP-GC filter in rentier series were identified as artifacts of the filter’s rigidity regarding asset price inertia, rather than signs of economic health.

- The study provides a solid methodological basis for future research on the ARoP and the dynamics of capitalism from a Marxist perspective.

PLANTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA Y OBJETIVOS

El artículo aborda la falta de un criterio teóricamente fundamentado para determinar qué actividades económicas deben incluirse o excluirse al estimar la tasa media de ganancia (TMG) marxista a largo plazo. El objetivo principal es proporcionar un criterio de decisión estándar marxista para la inclusión y exclusión de actividades económicas en el cálculo de la TMG, aplicado al caso de los sectores económicos de Estados Unidos entre 1960 y 2020.

MARCO TEÓRICO

El estudio se basa en la teoría marxista, específicamente en la definición marxista de trabajo productivo, su ubicación en el circuito del capital y su relación con la producción de plusvalía. Se hace hincapié en la distinción entre trabajo productivo e improductivo, así como en la diferencia entre consumo productivo e improductivo.

MÉTODOS Y TÉCNICAS

El estudio utiliza una variedad de técnicas econométricas y de análisis de series temporales avanzadas:

- Filtros de transformada wavelet de Daubechies con simetría aumentada.

- Descomposición en Modos Empíricos (EMD).

- Filtro Hodrick-Prescott incrustado en un modelo de componentes no observables (HP-GC).

- Diversas pruebas de raíz unitaria.

- Análisis de Componentes Principales (ACP) vía Descomposición en Valores Singulares (DVS) con Análisis de Distribuciones de Cola Pesada (Gamma/Weibull) y Teoría de la Información (Entropía).

- Regresión Horseshoe Regularizada (RHR) para selección de variables en entornos de alta multicolinealidad.

- Modelos de Factores Dinámicos (DFM) para validación estructural y detección de señales latentes.

RESULTADOS

- Se establecieron criterios para la inclusión y exclusión de sectores económicos en el cálculo de la TMG marxista.

- La aplicación de estos criterios a la economía estadounidense resultó en la exclusión de sectores como el comercio mayorista y minorista, finanzas y seguros, bienes raíces, y el gobierno.

- La TMG calculada con los sectores incluidos según los criterios establecidos mostró una tendencia decreciente a largo plazo, consistente con la teoría marxista.

- Los análisis econométricos revelaron una dualidad estructural: mientras la Regresión Horseshoe identificó un núcleo causal productivo alineado con la teoría del valor, el DFM y el ACP evidenciaron que la dinámica macroscópica fenomenológica está dominada por sectores rentistas (Bienes Raíces) y gubernamentales. Sin embargo, la tendencia decreciente de la Tasa de Ganancia se manifiesta en ambos núcleos.

- El análisis de ACP demostró que la varianza sistémica cualitativa (distribuciones Gamma/Weibull) es impulsada por un pequeño subconjunto de sectores (Top 10-15%), mientras que el grueso de la economía (PC1) representa ruido inercial o ‘movimiento browniano’.

CONCLUSIONES

- Los criterios propuestos para la inclusión y exclusión de sectores en el cálculo de la TMG marxista son válidos gnoseológica y econométricamente para el caso de la economía estadounidense entre 1960 y 2020.

- La investigación satisface la Teoría de la Coherencia de la Verdad, ya que la nueva proposición (criterios marxistas) armoniza lógicamente con la teoría y estadísticamente con la evidencia objetiva compleja.

- Los criterios demostraron consistencia objetiva, distinguiendo entre la esencia productiva (identificada por Horseshoe) y la apariencia rentista (identificada por DFM) en la dinámica económica capitalista.

- Se confirmó la tendencia decreciente a largo plazo de la TMG mediante filtros no paramétricos (EMD, Wavelets); las excepciones de tendencia plana observadas con el filtro HP-GC en series rentistas se identificaron como artefactos de la rigidez del filtro ante la inercia de precios de activos, y no como signos de salud económica.

- El estudio proporciona una base metodológica sólida para futuras investigaciones sobre la TMG y la dinámica del capitalismo desde una perspectiva marxista.